Article

Top 10 SaMD Job Boards & Regional Organizations

This blog contains Chapter 6 of the Orthogonal eBook titled: Digital Therapeutics (DTx): Accelerating Success Using Fast Feedback Loops. The following are links to each chapter of this eBook:

This section focuses on the U.S. market, which is the most advanced in some ways when it comes to the DTx industry. Before diving into US regulatory approaches, it’s useful to briefly highlight the regulatory approaches to DTx taken by two countries in Europe on the leading edge of DTx regulation: Germany and the United Kingdom (UK).

Germany passed the Digital Care Act in 2019, which enabled physicians to prescribe DTx to publicly insured patients (which includes 73 million people) and to receive reimbursement for DTx the same way as traditional pharmaceutical treatment. Germany’s Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices issued guidelines that digital health apps must meet to be eligible for this reimbursement. Germany has a “Fast-Track” path where DTx can be granted preliminary approval after an initial evaluation. After preliminary approval, the DTx company has 12 months to gather and present data on safety and efficacy.[1]

In the UK, the National Health Service (NHS) and The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) collaborated to develop an evidence standards framework for digital health technologies in April 2021.[2] Similar to the U.S. and Germany, UK guidelines group DTx into evidence tiers based on risk. Every DTx seeking reimbursement requires an economic analysis and budget impact analysis. The process for companies to seek re-approval after software updates (e.g., enhancements) remains unclear.[3]

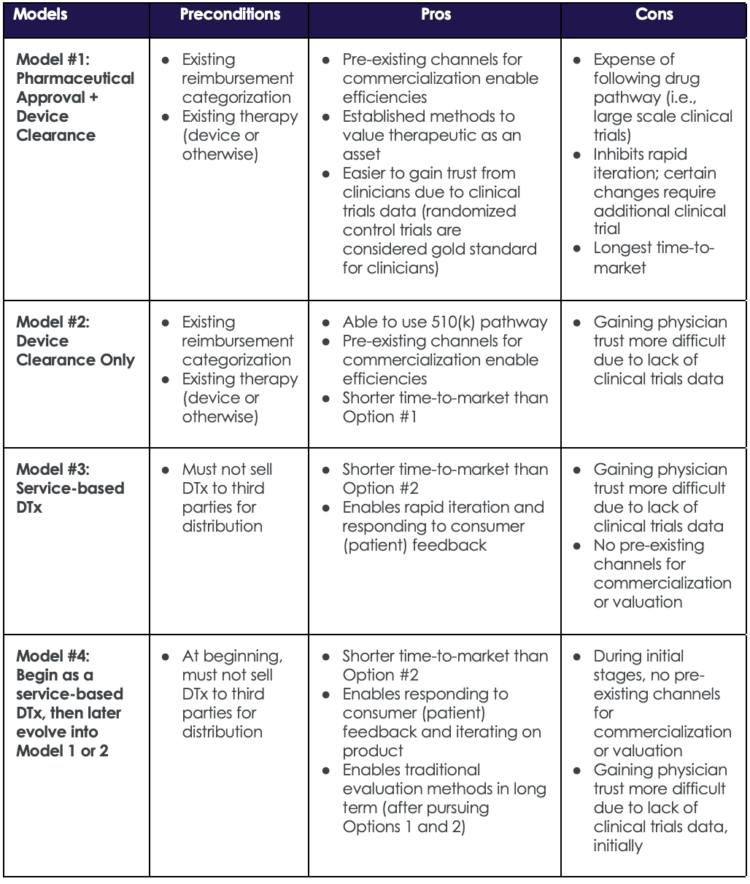

Now back to the U.S. The best approach for companies seeking to enter the DTx market is dependent on several factors. A variety of models are available and choosing one depends on the existing regulatory and reimbursement landscapes for the disease being treated. Table 2 below describes common go-to-market models for DTx.

Table 2: Common DTx Go-To-Market Models

The table below strives to provide a framework for thinking through common go-to-market models, but it is not comprehensive and at times may oversimplify some of the (many) complexities inherent in DTx business/regulatory strategies. For example, when a DTx is bundled with a traditional pharmaceutical (e.g., a pill), the go-to-market models become more complex. The table below includes examples for stand-alone DTx go-to-market models.

Table 2: Common DTx Go-To-Market Models

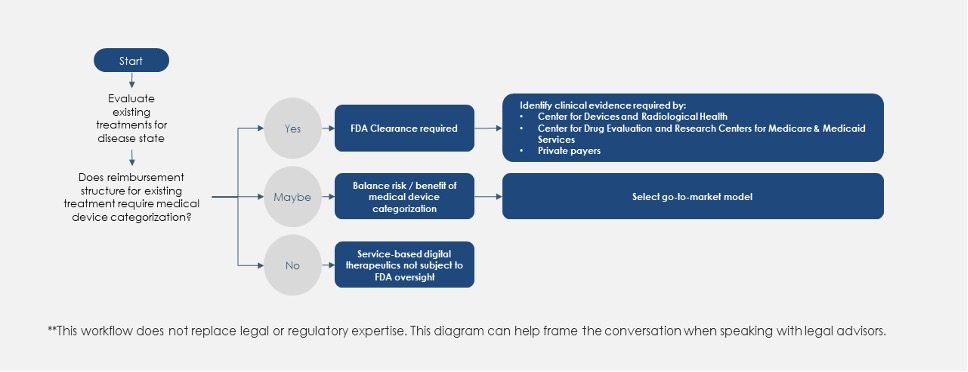

To select the optimal choice between these four go-to-market models, a DTx manufacturer must also determine the optimal strategy for regulatory categorization. Fig. 5 (below) presents a high-level process flow with key questions to help determine the most appropriate path to bring a DTx to market. Ultimately, what Fig. 5 boils down to deciding if the endgame for a DTx is to be classified as a medical device, a pharmaceutical or a combination of the two.

Regulatory Decisions Workflow for New DTx Products

The existing regulatory approach is useful for any product that will be classified as a medical device. For DTx, manufacturers may ask, “How can we become more like drug therapies?” There is a long-standing regulatory channel for evaluation and market placement of pharmaceutical therapies that requires companies to demonstrate their products’ safety and efficacy.

As soon as a company opts to take the medical device categorization route, the product becomes SaMD, which means that it is regulated—just as a medical device is—by the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH). Low risk devices (either Class I, or Class II where the FDA has decided to exercise enforcement discretion) do not require regulatory filing but are expected to follow FDA device quality systems regulations. Drugs are regulated by the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), and Biologics are regulated by the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER), different centers within the FDA.

Interactions with CDRH (and potentially other centers), as well as payors such as CMS must be factored into DTx development. Note that best practices that apply to SaMD will also apply to DTx. For example, companies that have a portfolio of different DTx products can reuse and scale their platforms in the regulatory process, thereby becoming a software platform company as well as a data and service company.

Usually, in the pharmacological clinical trials process, there is a long period in which the company is “de-risking” their product. Regulators, payors, and providers care most about ensuring the safety of the product. DTx companies that model the conventional drug approval process, i.e., engage in trials, develop an evidence base, move up the evidence curve, and de-risk the product over time, are already working in a way that the industry and regulators understand. Although this approach has slightly more upfront costs, it ensures that those that do take this route will have a channel for getting their product to market.

If a company decides that their go-to-market strategy includes categorizing their product as a medical device, the next step is determining the medical device class. The medical device class[4] is an important factor guiding the appropriate regulatory filing documents.

A premarket approval application is required for Class III devices. Class III devices present high risk to the patient and usually sustain or support life. DTx does not fall into this category so we did not describe Premarket Approval (PMA), although details can be found on the FDA website.[5]

Most DTx are categorized as Class I or Class II. Low risk devices (either Class I, or Class II where the FDA has decided to exercise enforcement discretion) do not require regulatory filing, but are expected to follow FDA device quality systems regulations. Class II devices for which the FDA is not exercising enforcement discretion do not require a PMA but do require a 510(k) Premarket Notification or De Novo clearance. For those who are not familiar with this nuance of medical device regulation, we have included brief definitions for the three filing pathways for obtaining FDA permission to bring a device to market.

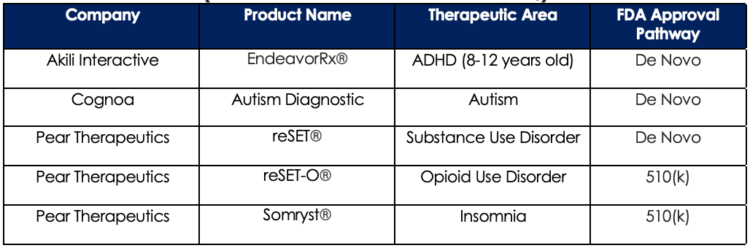

510(k) Premarket Notification:[6] Used for products that do not require a PMA, the 510(k) pathway includes a premarket submission to demonstrate that the device is substantially equivalent to an existing device on the market.

De Novo Clearance:[7] This pathway is used for DTx products with no similar device on the market with which the company can claim substantial equivalence.

Digital Health Software Pre-Certification Program:[8] This program, currently in pilot form, offers a view of how the FDA would like to manage DTx product approvals going forward. This program focuses on approving the product company, rather than the individual product, which in the world of software would be a specific version of the software product. This approach to approval will help DTx companies push updates to patients more efficiently. This is another example of the importance of setting up fast feedback loops.

Table 3 below (compiled by Exits & Outcomes[9] in their Prescription Digital Therapeutics Pipeline of Pipelines database) lists five DTx products that have received FDA approval as of August 2021 along with the pathway used to obtain their FDA-approved status.

Table 3: Prescription DTx Products with FDA Approval as of August 2021 (Data sourced from Exits & Outcomes)

Companies that follow the established drug and biologics model for generating clinical evidence look to gain value in commercializing their product in terms of easing physician acceptance, payor acceptance (with the promise of clearer reimbursement), and luring investment. This process requires presenting the DTx as a therapy equivalent to a drug or biologic, conducting trials, and reporting results, data, and clinical trials results to demonstrate efficacy. With this approach, reimbursement and market penetration can become easier.

Product iteration is still possible with this approach, and regulatory requirements around product updates are still evolving. For traditional pharmaceutical manufacturers, randomized controlled double-blinded trials are considered the gold standard. If this approach is used, software updates during the trial would not be feasible. One of the value propositions for modern software products in general is the ability to quickly gather performance and usage data, analyze this data, and test hypotheses to improve performance and usage. This “build-measure-learn” fast feedback loop process, with appropriate patient safety considerations, can be a key driver for product improvement, but one that is not compatible with currently prevalent clinical trials models. There have been some adaptive clinical trial models implemented, but more work is needed to unlock the full potential of SaMD and DTx. As the FDA continues to build regulatory requirements for DTx, allowing for feedback loops and iteration will be an important factor for regulators and manufacturers to consider.

Product iteration post-trial is also an important area of regulation. Compared to traditional pharmaceutical or medical device products, DTx is uniquely positioned to rapidly iterate on their product post-market. FDA guidance is still evolving, but companies will need to define the data collection process, define the types of changes that the company will be making to the product, and understand what types of changes will require filing for software updates to the product.

Given the complexities on this topic, Orthogonal is actively researching best practices and lessons learned for DTx iteration during and after clinical trials. (If you have opinions or insights on this question, please reach out to this eBook’s authors using the contact information provided at the end of this document).

DTx developers should consider whether they should take the FDA/device route, with the cost and time commitment of regulatory filing and clinical trials, or whether a more efficient path to reimbursement exists for a service-based framework. The following case study is one example of this.

For example, the company HabitNu offers pre-diabetes training to prevent the onset of type II diabetes. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) have already incorporated the HabitNu product into their own health programs, so there is no need for the company to take the FDA approval route. This is an example where a DTx product being brought to market quickly by staying within the guardrails of evidence-based research. Taking this route also provides fast product customization, essential for preventing/managing a condition that is closely associated with socio-cultural factors.

More specifically, in June 2018, HabitNu joined a handful of DTx products receiving full recognition from the CDC, as well as qualifying for reimbursement from CMS. As a preventative service, over 90 million people with or at risk for prediabetes can participate in the CDC- and CMS-sponsored National Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) for free with no insurance copay, using HabitNu’s technology to help motivate behavioral change and prevent the onset of prediabetes and diabetes.

HabitNu is not making specific medical claims about their product, but instead following the already defined outcome measures tied to the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code, so they are able to put out a non-medical device version of their product. This product is reimbursed as a service using existing insurance frameworks.

Final thoughts on the service-based route

Although this may be the best route for HabitNu, it is not the only way companies can innovate in this domain. HabitNu is still collecting data on their low-risk product; using this data, they may feel more comfortable to make claims about the product and seek regulatory approval via conventional processes.

Companies that select the service route as an initial strategy can choose to later opt into the regulatory route, which has certain advantages. Table 2 outlines pros and cons for four go-to-market model examples, including selecting the service route initially and later opting into the regulatory route.

This blog contains Chapter 6 of the Orthogonal eBook titled: Digital Therapeutics (DTx): Accelerating Success Using Fast Feedback Loops. The following are links to each chapter of this eBook:

References for Chapter 6 1. Brown D. Digital Therapeutics Regulation Explained (Including FDA, MDR, & DiGA). Smartpatient.eu. https://www.smartpatient.eu/blog/fda-mdr-digital-therapeutics-regulation-leading-countries. Published 2021. [Accessed December 6, 2021]. 2. Evidence standards framework for digital health technologies. NICE. https://www.nice.org.uk/about/what-we-do/our-programmes/evidence-standards-framework-for-digital-health-technologies. Published 2021. [Accessed December 6, 2021]. 3. Yan K, Balijepalli C, Druyts E. The Impact of Digital Therapeutics on Current Health Technology Assessment Frameworks. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fdgth.2021.667016/full. Published 2021. [Accessed December 6, 2021]. 4. Classify Your Medical Device. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/overview-device-regulation/classify-your-medical-device. Published 2020. [Accessed September 21, 2021]. 5. Premarket Approval (PMA). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/premarket-submissions/premarket-approval-pma. Published 2019. [Accessed August 23, 2021]. 6. Premarket Notification 510(k). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/premarket-submissions/premarket-notification-510k. Published 2020. [Accessed August 24, 2021]. 7. De Novo Classification Request. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/premarket-submissions/de-novo-classification-request. Published 2019. [Accessed August 24, 2021]. 8. Digital Health Software Precertification (Pre-Cert) Program. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/digital-health-center-excellence/digital-health-software-precertification-pre-cert-program. Published 2021. [Accessed August 24, 2021]. 9. Prescription Digital Therapeutics Pipeline of Pipelines - Exits and Outcomes. Exits and Outcomes. https://exitsandoutcomes.com/prescription-digital-therapeutics-pipeline-of-pipelines/. Published 2021. [Accessed August 20, 2021].

Related Posts

Article

Top 10 SaMD Job Boards & Regional Organizations

Article

Top 10 SaMD Events, Conferences & Webinars

Article

Top 10 SaMD Publications, Blogs & Media

Article

Top 10 SaMD Communities, Organizations & Working Groups