Article

Studying Compliance Burden to Improve SaMD Development

What This Pandemic Has Changed for MedTech, Connected Mobile Medical Devices (CMMD) and Software as a Medical Device (SaMD)

“Yet even as they walk through the valley of the shadow of death, chief executives and corporate strategists are beginning to look to the post-covid world to come. What they think they see, for good or ill, is an acceleration.”

—The Economist, April 11, 2020

The article “Sinking, Swimming and Surfing” in the April 11 issue of The Economist argues that the best way to understand COVID-19’s long-term impact on business is not to think of it as a game-changer. Instead, we can see this pandemic as a catalyst for speeding up long-term business trends that were in their early stages but already underway.

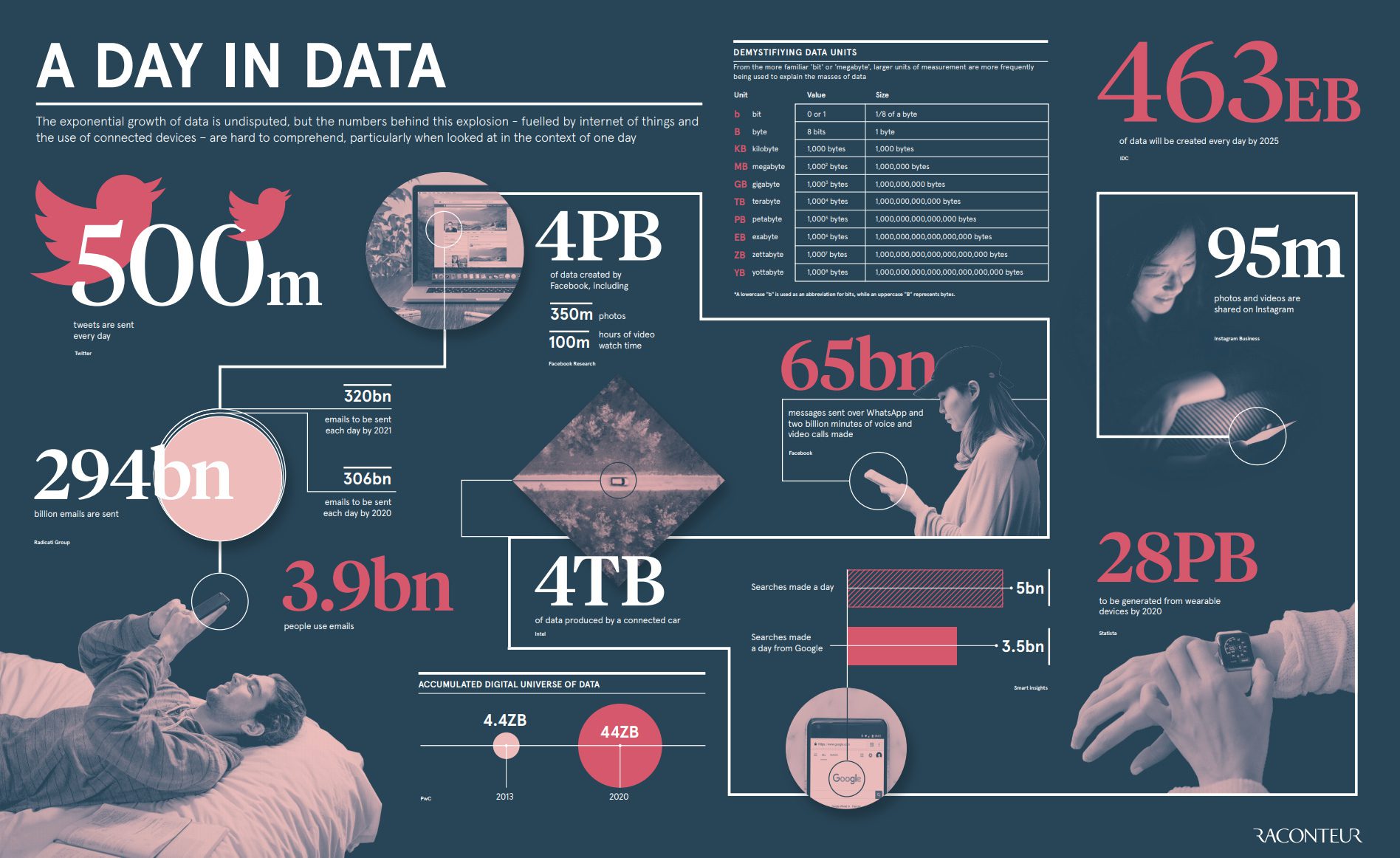

Specifically, the article discusses how the infusion of data-enabled services into ever more aspects of life is one of three essences of post-COVID acceleration because the range of the changes information technology makes possible will only increase.[1]

When it comes to healthcare, wellness, life sciences, and MedTech, we concur. The accelerated transformation of healthcare through data-enabled services will go on for years, if not decades. It will impact virtually every aspect of how we deliver, experience, and pay for healthcare.

For a quick refresher on the mathematics of acceleration, take this 9-minute course from Khan Academy.

In fact, we are willing to bet a pair of great tickets to a U2 concert in 2030 that by then, the first half of 2020 will be seen as the beginning of The Great Acceleration of Digital Health.[2]

Changes that modernize healthcare have historically spread slowly. In 1747, James Lind’s legendary in-field controlled trial on a British ship established the causal link between vitamin C deficiencies and scurvy. Unfortunately, it took nearly 50 years for British naval medicine to create a standard protocol based on this finding. In the meantime, there was a lot of avoidable suffering and death, not to mention the impact on commerce. But 50 years seems like a short period of time relative to the nearly 200 years it took for Lind’s pioneering use of a controlled clinical trial to become a standard medical research protocol.

Much of the reason for this is that our healthcare system is like Gulliver tied down by the countless Lilliputians serving as interlocking but competing sources of power across various interest groups that interact with a dizzying array of fragmented reimbursement players and structures, organizations providing care delivery, and non-aligned public policies.

Held back by this complex, competing and often contradictory web of parties and interests that adds up to a healthcare system, the promise of digital health has been slow in coming. Eric Jensen, whose company AVIA works on digital health initiatives with hundreds of health systems, writes that while digital health made good financial sense prior to the pandemic, there was a great deal of inertia:

“… In January 2020, despite these compelling arguments, digital still inspired discussion and debate, not investment and action. Leaders and boards of directors worriedly asked, ‘how might physicians respond to these changes?’ ‘How will digital solutions impact near-term revenue?’ ‘How will we fund these solutions?’ ‘How will these solutions integrate with our EMR?’ And they dithered.”

Jensen goes on to discuss what has changed in the first months of 2020:

“…Fast forward to today. It’s incredible how quickly the world has changed in 90 days. This is true in the economy, our personal lives, and especially true in digital health. The magnitude of the change is best encapsulated in an image that popped up on my Twitter account in the last week:”

As we have seen multiple times in recent history, watershed moments such as WWII, the 1970s Energy Crisis, 9/11, and the Great Recession necessitated the rapid change of key assumptions, rules, and structures that had previously been seen as largely immovable constraints.

Today, the need to address two interlocking but often competing goals has opened up new doors for digital health:

In a bid to avoid the transmission of COVID-19 between people, many physical interactions that are the bedrock of our health system have been severely curtailed, including elective surgeries. In this crisis, any service is elective until the risk to the patient of not conducting the surgery is greater than the risk of COVID-19 infection. This includes appointments at the doctor’s office, non-COVID-19 diagnostics, and in-clinic therapy administration. To give just one example of the impact, the American Hospital Association estimates that, as a result of canceled hospital services due to the COVID-19 pandemic, US hospitals not owned by the federal government will lose over $160 billion in revenue between March and June of 2020.

This slowdown is also affecting medical device and pharmaceutical companies providing devices and drugs whose use is tied to these elective services. When hip replacements and heart and brain surgeries are down 65% to 80%, and physician-administered injectable drugs are not being administered because patients stop coming to their doctors’ offices, these devices and drugs collect dust in storage closets at clinics and in warehouses.

In more bad news for these medical manufacturers, the next generation of many devices and drugs are also being delayed because clinical trials heavily rely on in-person visits to medical facilities. Dexcom, for example, has halted the trial of their G7 continuous glucose monitor. Although the full impact of a related factor is not known, delays in clinical trials are being compounded by some degree of delays in FDA regulatory approval as regulatory staff are being shifted to COVID-19 related oversight

While hospital systems are not buying large capital equipment or performing hip replacement surgeries, they are spending money on things that help them address COVID-19 and its fallout. Current growth areas in healthcare spending include point of care diagnostics, telehealth, remote monitoring, and remote treatments.

For telehealth, the challenge used to be to get hospital systems, providers, and patients just to try it out and then to ensure the users have enough of a positive experience that they would want to use it again. Now, the challenge for providers is to scale their telehealth offerings to match the demand. Patients and providers are motivated by a desire to provide or receive treatment without risk of COVID-19 infection, and health systems have obliged. By one count, insurance claims for telehealth increased 4,347% nationally when comparing March 2019 and March 2020. To give an example from one provider, Medstar, which operates a 10-hospital network in the Washington, DC, and Baltimore areas, telehealth volume has jumped from two visits per week to a high of 4,000 per day.

This rapid acceleration of telehealth has been facilitated by state and federal regulators and public and private payers quickly expanding the range of coverages for telehealth, allowing providers greater flexibility to work remotely, and easing licensure barriers to allow providers to treat patients across state lines.

As with any major change, there have been both positive and negative consequences of this shift. On the one hand, hospital staff has found that telehealth visits can replicate many of the traditional in-person services, reducing the risk and burden on patients and families, and allowing doctors and nurses to redefine their workloads, focusing on in-person care on the most critical cases.

On the other hand, the shift to telehealth has unintended consequences that either need to be mitigated or accepted as the price of change. For example, psychiatrists have planned their workloads and schedules assuming that some natural level of patients canceling appointments would provide them with time during the day to catch up on notes, order prescriptions, and generally take a few minutes to unwind from a job that can be emotionally intense. Some psychiatrists are now reporting that with telehealth-based practice, far fewer patients are canceling their appointments and that the overall intensity and length of their days is increasing as a result.

While a telehealth visit enables new options for patient/provider interaction, telehealth is still limited by the inability of phone calls or video chats to replicate certain hands-on, physical interactions such as a provider using an otoscope to visually diagnose an ear infection or needing a phlebotomist to safely and properly draw and prepare blood for lab tests.

Over the last few years, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has begun to roll out reimbursement for certain services delivered to the home. Providers have been trying out more remote monitoring. But since COVID-19, many more providers have started using remote monitoring platforms to provide care for patients in their own homes. Regulators have also shown pandemic-necessitated flexibility in allowing remote monitoring with digital health devices.

According to Ethan Booker, MD, medical director of Maryland-based MedStar, COVID-19 is providing

“the opportunity to move from a highly scheduled and (episodic) experience to a much more relational experience for both patients and providers…. remote patient monitoring services provide a continuous, data-rich platform that connects providers to patients at any time, rather than just when the patient comes to the provider…

Having learned how to manage patients with COVID-19, providers can now pivot to manage patients with chronic care needs, or those who’ve just been released from the hospital, or those who frequently visit the hospital, in their homes.”

Some relevant examples of remote monitoring include the following:

At-Home Heart Monitoring

At-home heart monitoring through connected devices like those from iRhythm, AliveCor, and PhysIQ was already becoming more prevalent as a way to give patients and clinicians a clearer picture of heart health in real-time. Each of these companies sees a sizable uptick in customer adoption of those services since the start of the crisis.

Orthogonal client PhysIQ, in particular, has received broadened FDA labeling for their pinpointIQ® continuous remote monitoring solution, in which they will be using their proprietary Multivariate Change Index (MCI) to proactively monitor homebound patients with or vulnerable to COVID-19.

Diabetes Management

Diabetes management is another area where the use of digital health has accelerated. Diabetes patients are at higher risk of having worse outcomes from a COVID-19 infection, so shifting more diabetes care from the clinic to the home was an easy case to make. Because of the importance of real-time glycemic data in diabetes care, there are already a number of tools that allow continuous real-time access to patient-generated health data.

The Center of Digital Health and Innovation at UCSF has helpfully provided a useful description of the value of remote diabetes care and the steps they have taken to successfully implement it. We have this lengthy excerpt because it provides a concise description of the kinds of changes that can be generalized to facilitate remote monitoring and care for patients with conditions besides diabetes:

“We are uniquely poised to use diabetes technology for what it is supposed to allow: remote, fully connected diabetes care…[Here are] the most important steps we have taken [at UCSF], to allow optimal diabetes care alongside the rapid increase in our volume of telehealth visits. Within the past week at UCSF, video visits have risen from around 2% of all ambulatory visits to nearly 50% of all visits on a daily basis.

1. Encourage patients to start sharing their diabetes data with the clinic. For patients using glucometers: encourage them to start using Tidepool. Patients can upload data from their glucometers at home using the Tidepool Uploader. With an invitation from the clinic, patients share their data with providers. Most glucometers are supported, which eliminates the need to use multiple different software platforms.

For patients using continuous glucose monitors and/or insulin pumps: encourage them to start sharing data on Tidepool, or alternatively on device-specific software platforms (e.g., Dexcom Clarity, Medtronic Carelink, Abbott LibreView, Tandem T-Connect).

2. Discuss and interpret diabetes data with the patient. Now that patients are connected to continuous data sharing, CGM data can be viewed remotely during a scheduled video visit. Use screen sharing so patient and provider are reviewing the same information—make it a teachable moment!

3. Interpret diabetes data outside of scheduled video visits. If patients contact the clinic with diabetes management questions, providers or their team members can review relevant glucose data online and provide guidance.

4. Seek reimbursement for data interpretation. Interpretation of 72 hours of CGM data can be billed using CPT code 95251; remote monitoring of glucose data from fingersticks is also billable with CPT codes 99091 or 99457.

5. Capture patients’ use of diabetes devices at a clinic level. Who uses a continuous glucose monitor? Who uses an insulin pump? What brand? This device-specific information enables a clinic to do proactive patient outreach. Targeted patient communication may become increasingly important to convey clinical messages during the pandemic.”

In-Patient Telemedicine and the Virtual ICU

Not all of the digital health innovations that are occurring are outside the hospital. One solution that may offer benefits long after the pandemic has passed is in-patient telemedicine, such as a Virtual ICU solution. Today, in an ICU ward designated for infectious COVID-19 patients, the Virtual ICU integrates EMR data with data coming off the devices attached to and monitoring patients in an isolation ward. In addition to providing easy access in real-time to those two often distinct sets of data, a Virtual ICU integrates video conferencing between the providers working on the ICU floor, those right at the patient’s bedside and providers across other locations. At its best, a Virtual ICU allows hospitals to assemble highly-coordinated care teams for each patient that don’t have to be physically present at the patient’s bedside. This kind of time savings helps providers be more efficient and reduces the chances of patients and providers passing infections between each other. Recognizing the value of this idea major ventilator manufacturers have rapidly added remote monitoring capabilities for their devices over the last few months.

Another interesting use case for remote digital health is offered by our colleague Dr. Alex Langerman and his teammates at ExplORer Surgical. Their startup is experiencing rapid growth this year by using video conferencing capabilities on iPads, instructional TV screens on the OR walls, and detailed computerized workflow checklists to help medical device makers collect better data during clinical trials for devices used in the operating room, such as implants. Device makers are also now using this technology to remotely provide the kind of training and technical support to surgeons using devices that a representative might have once provided by standing in the OR. Hospitals are now far less eager to have additional “guests” in an OR during surgery, and device makers are finding that they can provide much more consistent, high-level support and guidance to surgeons, using remote, real-time device experts who can observe the procedures and have real-time conversations with the surgeons to better understand how the products are (and aren’t) working outside of the laboratory.

A recent article in Crunchbase highlights the impact of COVID-19 on clinical trials in terms of patient recruitment, provision of treatments, and ongoing monitoring, as well as some of the long-term opportunities this presents:

“COVID-19…threw a wrench in the traditional method of clinical trials, in which participants usually travel to a clinical site for an in-person evaluation. This is causing principal investigators and research staff to find other ways to keep participants connected with studies…

Even before the pandemic, some in the clinical trials sector was pushing for the addition of virtual components, such as wearables for data collection throughout the day. Others sought the adoption of decentralized clinical trials, those executed through telemedicine and mobile or local health care providers.”

Prior to the epidemic, proponents of virtual or decentralized clinical trials were still trying to convince the industry to migrate to more remote and digitally-enabled clinical trials. Today this is a much easier case since the alternative to a virtual clinical trial is no longer an in-person clinical trial (which is seen as a known quantity and therefore less risky) but no clinical trial at all.

While some companies have had to cut short or postpone trials, others have been able to quickly transition. For example, one of our customers has a digital therapeutic for chronic disease treatment. After the outbreak began, they were able to quickly pivot their clinical trials approach and transition to a 100% virtual trial, minimizing the impact on their product development and launch life cycle. Following the FDA’s new guidance on the Conduct of Clinical Trials during COVID-19, about 75% of their sites were able to switch to enrolling subjects via telemedicine.

A number of years ago, the FDA recognized the opportunity the digitally connected world provided for capturing real-world data and evidence that could be used to evaluate and improve the safety and effectiveness of products they regulate. Every professional at the FDA was already personally experiencing the growth of smartphones and tablets, social media, cloud-based services, and fitness trackers and seeing applications of those technologies changing their own lives. So it was not too much of a stretch to think about how these burgeoning collections of user-based data might be applied to improving safety and effectiveness across the full product life cycle of medical devices.

“The use of computers, mobile devices, wearables and other biosensors to gather and store huge amounts of health-related data has been rapidly accelerating. This data holds the potential to allow us to better design and conduct clinical trials and studies in the health care setting to answer questions previously thought infeasible. In addition, with the development of sophisticated, new analytical capabilities, we are better able to analyze these data and apply the results of our analyses to medical product development and approval.”

Forward-thinking device makers were also starting to recognize the potential value of RWD/RWE both for the safety and effectiveness purposes recognized by the FDA, as well as the ability of that data to demonstrate comparative effectiveness for reimbursement purposes. Finally, some began to see this data as a way to learn more about how their products were being used on an ongoing basis and began to incorporate this data into new connected services for patients and clinicians. They also began to gather these vast, rich data troves to use as a competitive edge to drive successful product updates and new product development.

This interest in RWE has been reflected in multiple programs, including the following:

One of the more interesting projects that the FDA has been working on is an expansion of the RCT DUPLICATE program that uses RWD to predict randomized trial results before they’re completed. Aetion is the FDA’s partner in this program, and according to their CEO, Carolyn Magill, “Data collected from the front lines of clinical care can often provide a more complete picture on how treatments affect patients not represented in clinical trials, but the regulatory process must ensure transparency.”

This program is now being used by the FDA to gather information on diagnostic and treatment patterns for COVID-19 and help the agency better understand the natural course of the novel coronavirus. According to the FDA’s principal deputy commissioner, Amy Abernethy, “The FDA is approaching the generation of real-world evidence for COVID-19 with a sense of urgency to learn what we can, as soon as we can, from patients who are receiving care right now…. We also recognize that COVID-19 is a dynamic situation. We can use current data and learn what decisions we can confidently make now, and we can learn what we’ll need to do in the future as more data become available.”

Similarly, here at Orthogonal, we are working with an established medical device firm to apply state-of-the-art tools for getting data-driven insights into patient behaviors, both to provide better behavioral “nudges” to improve health outcomes and to speed the development of ever better products to help those patients.

**

In our next blog post, we take a look at what we think will be in store after this pandemic for MedTech, connected mobile medical devices (CMMD), and software as a medical device (SaMD).[3]

**

Our favorite inbound messages after a new post do not start with, “Great post. Keep up the good work.” Our favorites are the ones that start with, “I read your post and I disagree when you said x because you are not taking y and z into consideration.”

Our ideas are ultimately strengthened by open, candid conversations. We’d love to hear from you about this blog post and the ones in the pipeline. Do you agree with our take? Disagree? Have questions? Have you read an article that we should read? Feel free to reach out to our CEO, Bernhard Kappe or VP, Solutions & Partnerships, Randy Horton.

In return, we will look for ways to share more blogs, personalized insights, content, and introductions that are highly relevant to your work.

We plan to dive into the best of what we are reading and hearing about in the industry. Topics we plan to address include the following:

With a strong sense of urgency, Orthogonal is actively developing a point of view of what this pandemic and its aftershocks mean for medical device firms and their innovators creating connected mobile medical devices (CMMD) and software as a medical device (SaMD).

Given the unsettling and largely unexpected acceleration of change in 2020, we see an opportunity to add value to our industry by synthesizing and sharing the best of what we are learning on an ongoing basis. In the end, it’s important that we all succeed because every person in our lives is a customer of healthcare and life sciences.

Orthogonal is a software developer for connected mobile medical devices (CMMD) and software as a medical device (SaMD). We work with change agents who are responsible for digital transformation at medical device and diagnostics manufacturers. These leaders and pioneers need to accelerate their pipeline of product innovation to modernize patient care and gain competitive advantage.

Orthogonal applies deep experience in CMMD/SaMD and the power of fast feedback loops to rapidly develop, successfully launch, and continuously improve connected, compliant products—and we collaborate with our clients to build their own rapid CMMD/SAMD development engines. Over the last eight years, we’ve helped a wide variety of firms develop and bring their regulated/connected devices to market. If you need help building your next CMMD or SaMD, or to learn more, contact us or call us at (866) 882-7215.

**

Bernhard Kappe is Founder and CEO at Orthogonal. You can email him at bkappe@devorthogonal.wpengine.com

Randy Horton is VP of Solutions and Partnerships at Orthogonal. You can email him at rhorton@devorthogonal.wpengine.com

Footnotes:

Related Posts

Article

Studying Compliance Burden to Improve SaMD Development

Article

Lifestyle Integration for Medical Devices

Article

CEOs and other Digital Health Experts on SaMD in 2020

Article

Looking Back at a Pioneer in DTx and SaMD – Propeller Health in 2013