Article

Help Us Build an Authoritative List of SaMD Cleared by the FDA

This blog is the first in an ongoing series exploring the crucial linkage between successful Software as a Medical Device (SaMD) and patient engagement.

The overall theme of this series is that SaMD (and other permutations of connected medical devices) are poised to have a huge impact on the outcomes and ROI that we get as a nation for our healthcare. Or not.

If connected medical devices can make a significant difference for health conditions like diabetes, liver disease, heart disease, and pulmonary disease, the benefits could be huge. But to get there, patients need to be self-driven to take advantage of what these digital tools have to offer.

Today, patients have consumer-grade expectations for every interaction they have with the healthcare system. Patients (i.e., you, me, and everyone else we know) have come to expect that they can engage with products and services for healthcare and wellness in the same manner that they now conduct their shopping.

Success in this domain will require medical device makers to develop and flex a new set of muscles that they historically have not had to think much about. In the end, they need to create top-flight, consumer-grade patient experiences. Experiences that are so compelling that they successfully compete for our attention with Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, and texting. If medical device makers don’t create engagement at that level, patients will spend their time on non-healthcare activities such as hanging out on Facebook, Instagram, or TikTok. And we’re not going to move the needle on healthcare costs and outcomes (not to mention medical device maker profits) by churning out a bunch of also-rans.

In the end, success in this promising and growing area that will come down to the extent to which the people providing these connected devices and services can create a compelling user experience that engages people as patients and caregivers to step up and take control of their of health destinies, while at the same time empowering them to do so by putting powerful information tools in their hands.

At one time, our collective image of the US healthcare system (if not necessarily the reality of the actual healthcare system) evoked some fairly traditional ideas about medicine, how patients received it, and who delivered it to them.

At the risk of oversimplification, patients were passive players in their own healthcare, simply awaiting instructions for the one right treatment provided by a singular trusted expert physician.

Generally, popular images from this era involved a patrician (white male) physician, supported by an (also white) female nurse, who asked the patient a few questions and then spoke to the patient in an unhurried tone, dispensing advice about behavior changes (e.g., get more sleep) and prescribed therapeutics (including some true marvels of the industrialized economy). At least in collective memory, the patient would gladly accept this advice as the answer to their health needs, go home, and follow these instructions.

As proof points, we offer examples of popular healthcare-related artwork (Curious George and Norman Rockwell) from post-WWII America. The middle picture even pokes fun at the idea of the expert physician by showing a boy verifying his doctor’s credentials on the wall while waiting for a shot in the rear.

In the 1980s, the Syms clothing retail chain coined the now legendary marketing tagline, “An educated consumer is our best customer.”

Over the last several decades, several changes in our healthcare system and our larger society have taken this concept and basically put it on some powerful steroids.

Our understanding of the disease and our options for treating it have dramatically increased. Since the late 1970s, the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) system has had a 19x increase in procedure codes and a 5x increase in diagnostic codes.

The healthcare system’s financial incentives have been shifting from a volume-based model, where patients and insurers pay for healthcare products and services rendered, to a value-based model. However, this trend could be charitably characterized as uneven and moving forward, not in a steady progression but instead in fits and spurts.

The shift to value-based medicine is also leading to a much greater emphasis on primary care and preventative medicine. This is logical causation since the most effective therapeutics are the ones that prevent illness from even beginning or diagnose and treat it when it is still in a nascent state.

As a result of the Internet’s explosive growth and the accelerated adoption rate for smartphones, connected resources are fully embedded as a part of daily living and our overall lifestyles. As in many other domains of our lives, such as education, entertainment, and religion/spirituality, the combined rise of smartphones, cellular networks, and the Internet has greatly changed the way we approach our own healthcare.

The rise of Internet-enabled patient self-education has both positive and negative aspects. For example, to go back to the Syms metaphor, an educated customer is only a better customer if it’s a quality education. A world of information, misinformation, conflicting information, and out-of-context information is all equally available at their fingertips. In literally one second, Google can provide 432 million search results for diabetes,102 million search results for asthma, and 5.2 billion search results for COVID-19! Often, we rely on Google’s algorithms to tell us which content we should trust instead of seeking the guidance of a medical professional who is familiar with our own health and lives.

Patients now expect their access to healthcare, wellness products, and services to mirror their retail shopping experience. A good description of what patients/consumers expect from retail comes from Marketo’s Modern Marketing blog, which describes “a seamless experience, regardless of channel or device. Consumers can now engage with a company in a physical store, on an online website or mobile app, through a catalog or social media. They can access products and services by calling a company on the phone, using an app on their mobile smartphone, a tablet, a laptop, or a desktop computer. Each piece of the consumer’s experience should be consistent and complementary.” (This kind of seamless experience is referred to as omnichannel.)[1]

Medical devices have evolved from typically being stand-alone pieces of machinery into internet-connected devices that can communicate with patients, providers, and medical device manufacturers on an ongoing basis.

Frequently, especially in the case of devices used by the patient in their daily lives (outside of a clinic or hospital), this communication happens through a patient’s personal smartphone using a downloadable app specifically designed to manage the device. Upstream from the smartphone, your doctors and medical device makers can access this same data and gain insights by fusing it with your other medical data and algorithms that consult a wide scope of clinical knowledge. When your connected glucose pump talks to a companion app on your smartphone, and that app in turn talks to your physician’s office and medical records, it’s using the same technologies as when your Spotify app downloads music from the cloud and plays it wirelessly using an external Bluetooth speaker.

These medical device apps also have access to a powerful suite of hardware for data input and output (I/O), including cameras, microphones, and sensors that measure acceleration, gyromotions, proximity, direction with a compass, and barometer. While I/O tools are often not “clinical grade” and, therefore, can’t replace all of the hardware in a medical device, they can be used in other ways to support the patient’s use of a connected medical device.

So what will it look like when healthcare organizations recognize these changes and begin to design solutions that address them head-on instead of making cosmetic accommodations? A large number of organizations are trying to figure this out, ranging from digital health startups to large, established healthcare providers.

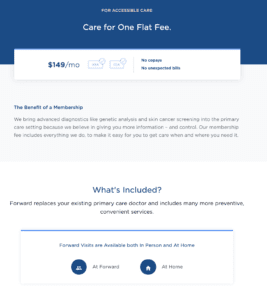

For example, Forward Health is a Bay Area startup with leadership from an array of technology firms, including Google and IDEO. Forward is a digital health update on the concierge primary care concept. A patient pays a flat rate of $250/month for unlimited patient visits, mirroring payment plans that consumers commonly use for online subscriptions for software tools and content.

The model leans heavily on a preventative model that sits on top of primary care. With the use of technology, sensors and virtualized patient records, the care provider and patient can more closely align on preventative care programs.[2]

Forward does not offer comprehensive care that includes more expensive and specialized treatments such as surgery or cancer care. So patients still need to have private insurance to ensure access to a full range of care. Time will tell if this model evolves into what is desired by most “users”, namely full-virtualized care, including therapy or management support, completely replacing the traditional healthcare insurance and delivery model.

Another trend we expect to see amplified is the use of connected medical devices to shift the delivery of screening, prevention, and chronic disease management to locations that are already a part of the patient’s lifestyle and daily routine.

Politico recently profiled a program that is tackling this challenge:

“A group of Los Angeles-based investigators is taking a new approach to controlling blood pressure in a bid to address the disproportionate burden heart disease places on Black men. The CDC estimates as much as a third of the gap in life expectancy between white and Black males is due to cardiovascular illness.

The solution involves bringing pharmacists — and now virtual blood pressure checks — to neighborhood barbershops, where they help manage medications and track how well hypertension is controlled. The program was fine-tuned over five years, with researchers testing whether care delivered in the right place, in partnership with trusted members of the community, can be effective.”

A mobile cart with a video hookup and a blood pressure cuff used in barbershops in Los Angeles. | Cedars-Sinai Medical Center

A mobile cart with a video hookup and a blood pressure cuff used in barbershops in Los Angeles. | Cedars-Sinai Medical Center

This Cedars-Sinai program is moving the needle on healthcare outcomes by acknowledging that the best way to connect with and help patients with chronic disease may not be to get them to come to providers settings such as a doctor’s office or pharmacy. Instead, they use a combination of in-person and virtual care that includes connected medical devices at a venue that is already part of the patients’ lives.

So if yesterday’s patient is today’s patient/consumer, what can we do to empower these consumers to take excellent care of their single most important physical possession, their own bodies? How can we help patients treat their bodies like one-of-a-kind, priceless objects that can never be replaced when damaged or lost?

In the next blog in this series, we’ll discuss two related tools in the digital health delivery toolkit that can help put patient/consumers on that path to treating their bodies as a priceless possession: patient engagement and Software as a Medical Device (SaMD).

Adrian Pittman is a Director of Product Design at LinkedIn. Previously, he was the Director of User Experience and Human Factors at Orthogonal and a design leader at Google. You can email him at adriandpittman@gmail.com

Bernhard Kappe is Founder and CEO at Orthogonal. You can email him at bkappe@devorthogonal.wpengine.com

Randy Horton is VP of Solutions and Partnerships at Orthogonal. You can email him at rhorton@devorthogonal.wpengine.com.

Related Posts

Article

Help Us Build an Authoritative List of SaMD Cleared by the FDA

Article

SaMD Cleared by the FDA: The Ultimate Running List

White Paper

Software as a Medical Device (SaMD): What It Is & Why It Matters

Article

Patient Engagement & UX for Bluetooth Medical Devices